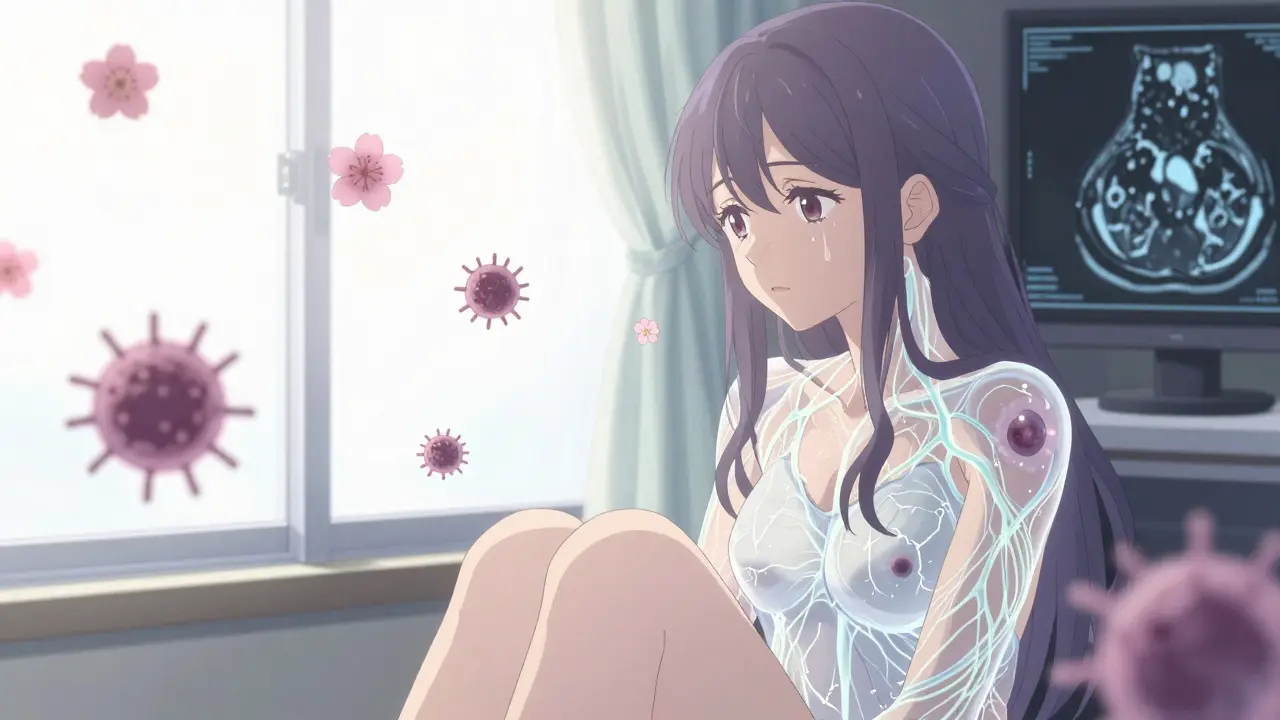

Multiple sclerosis is not just a neurological condition - it’s a silent war inside the central nervous system. Your body’s own immune system, designed to protect you, turns against the protective coating around your nerves. That coating, called myelin, is what lets signals race from your brain to your muscles, your senses, and your organs. When it’s damaged, those signals slow down, stutter, or stop entirely. The result? Fatigue so deep it feels like your bones are made of lead. Vision that blurs for no clear reason. Numbness in your limbs. Trouble walking. Words that won’t come out even when you know them. This is multiple sclerosis - and it’s more common than most people realize.

What Actually Happens in Your Body With MS?

At its core, MS is an autoimmune attack on myelin. Imagine your nerves as electrical wires. Myelin is the plastic insulation wrapped around them. Without it, the signal gets weak or short-circuits. In MS, immune cells - mainly T-cells - cross the blood-brain barrier and start chewing up that insulation. The damage leaves scars, or lesions, which show up as bright spots on MRI scans. These lesions aren’t just random spots; they’re evidence of inflammation, nerve damage, and eventually, permanent scarring.

It’s not just the myelin that gets hit. Over time, the nerve fibers underneath (axons) start to break down too. That’s why MS gets worse over time - it’s not just a flare-up, it’s cumulative damage. The body tries to repair the myelin, but it’s not good enough. Oligodendrocytes, the cells that make myelin, can’t keep up. That’s why early treatment matters so much. Slowing the immune attack early can save nerves from permanent destruction.

Who Gets MS - And Why?

MS doesn’t pick its victims randomly. Most people are diagnosed between ages 20 and 40. Women are two to three times more likely to get it than men. And geography plays a huge role. If you live near the equator, your risk is low - about 30 in 100,000. But if you’re in Canada, Scotland, or Scandinavia? That number jumps to 300 in 100,000. The further you are from the equator, the higher your risk.

Why? Sunlight. Vitamin D. Studies show people with low vitamin D levels (below 30 ng/mL) have a 40% higher chance of developing MS. Sunlight exposure isn’t just about mood - it’s a biological trigger. Genetics also matter. If you have a close relative with MS, your risk goes up. The HLA-DRB1*15:01 gene variant alone triples your chances. But genes alone don’t cause MS. Something else has to flip the switch.

That something might be Epstein-Barr virus. Nearly everyone with MS has had EBV - the virus that causes mono. A 2022 Harvard study found people who had infectious mononucleosis were 32 times more likely to develop MS later. But not everyone with EBV gets MS. So it’s not the virus alone - it’s the virus plus genetics plus low vitamin D plus other unknown factors. MS is a perfect storm, not a single cause.

The Four Types of MS - And What They Mean

Not all MS is the same. There are four main patterns, and they shape how the disease progresses and how it’s treated.

- Clinically Isolated Syndrome (CIS): This is your first neurological episode - maybe blurry vision, or numbness on one side. It lasts at least 24 hours. If your MRI shows lesions typical of MS, you have a 60-80% chance of developing full MS within 10 years.

- Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS): This is the most common type - 85% of cases. You get attacks (relapses) where symptoms suddenly get worse, then you recover partially or fully (remission). Without treatment, people have about 0.5 to 1 relapse per year.

- Secondary Progressive MS (SPMS): After 10 to 25 years, about half of RRMS patients start to decline steadily, even without clear relapses. This is when damage builds up faster than the body can repair.

- Primary Progressive MS (PPMS): About 15% of cases. No relapses. Just a slow, steady worsening from day one. It’s harder to treat because inflammation isn’t as obvious.

Knowing which type you have guides treatment. RRMS responds best to immune-modifying drugs. PPMS needs different strategies focused on slowing progression, not just stopping flares.

Diagnosis: It’s Not Just One Test

There’s no single blood test for MS. Diagnosis is a puzzle. Doctors use the McDonald Criteria - a set of rules built around MRI findings, spinal fluid tests, and clinical symptoms.

First, an MRI. A 3 Tesla machine picks up 30% more lesions than older 1.5 Tesla scanners. They look for lesions in at least two different areas of the brain or spinal cord (dissemination in space) and lesions that appeared at different times (dissemination in time). That’s key. One lesion? Could be anything. Two lesions, one old, one new? That’s MS.

Then, a spinal tap. They check for oligoclonal bands - abnormal proteins in spinal fluid that suggest immune activity in the brain. Blood tests rule out other conditions like Lyme disease or vitamin B12 deficiency.

It takes time. Most people see three to five specialists over six to twelve months before getting a firm diagnosis. In the U.S., the initial workup can cost $2,500 to $5,000 out-of-pocket - even with insurance. That’s why many wait too long to get tested.

Treatment: Slowing the Damage, Not Curing It

There’s no cure for MS - yet. But there are more treatments now than ever before. Over 20 disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are approved. They don’t make you feel better overnight. Their job is to reduce relapses and slow long-term disability.

These drugs fall into six categories:

- Injections: Glatiramer acetate, interferons. Cheap, but many people stop because of flu-like symptoms or painful injection sites.

- Oral pills: Fingolimod, teriflunomide. Easier to take, but come with risks like liver damage or increased infection.

- Infusions: Ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, ublituximab. Given every few months. Very effective - 50% fewer relapses in trials. But they suppress the immune system, so you’re more vulnerable to infections.

Annual costs range from $65,000 to $87,000. But 90% of U.S. patients get financial help from drug companies. Still, many can’t access these drugs in low-income countries. Half the world has no access to any DMTs.

One big problem: side effects. A 2023 survey found 42% of people quit injectable treatments within a year because of pain, swelling, or constant flu symptoms. That’s why newer drugs - like monthly pills or infusions every six months - are changing the game. Less hassle, better adherence.

Living With MS: Fatigue, Brain Fog, and the Hidden Struggles

MS isn’t just about walking. The biggest complaint? Fatigue. Not regular tiredness. A crushing, bone-deep exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep. On MS support forums, 78% of 150,000 users say it’s their worst symptom.

Then there’s brain fog. People describe it as trying to speak but the words vanish. Forgetting names. Losing train of thought mid-sentence. One Reddit user wrote: "I know the word. It’s right there. But my brain won’t let me grab it." That’s cognitive dysfunction - and it’s real.

Work becomes harder. 82% of employed people with MS need accommodations. Flexible hours. Remote work. Shorter days. These aren’t luxuries - they’re survival tools. Many lose jobs because employers don’t understand invisible symptoms.

Physical therapy helps. Balance training cuts falls by 47%. Heat sensitivity is another hidden issue - hot showers, summer heat, even a fever can make symptoms worse. That’s Uhthoff’s phenomenon. It’s temporary, but terrifying when it happens.

The Future: Remyelination, Stem Cells, and Hope

Research is moving fast. Scientists aren’t just trying to stop the immune attack anymore - they’re trying to fix the damage.

One exciting area: remyelination. Drugs like opicinumab are being tested to help the body regrow myelin. In Phase II trials, patients showed 15% improvement in nerve signal speed. That’s huge. If it works, it could reverse disability, not just slow it.

Stem cell therapy is another frontier. Over 120 clinical trials are underway. Some patients have had their immune systems wiped out with chemotherapy, then rebuilt with their own stem cells. Early results show long-term remission in aggressive MS cases.

Gut health is getting attention too. The microbiome - the bacteria in your gut - may influence immune behavior. Early trials with fecal transplants show a 30% drop in inflammatory markers. It’s early, but it’s promising.

And prognosis? It’s getting better. In Sweden, 70% of people diagnosed after 2010 are still walking without help 20 years later. That’s up from 45% for those diagnosed before 1990. Early diagnosis and early treatment are making the difference.

What You Can Do Now

If you’ve been diagnosed, start treatment as soon as possible. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. The goal isn’t to feel perfect - it’s to protect your future.

Check your vitamin D. Get it tested. If it’s low, supplement. Get sunlight safely. Stay active. Walking, swimming, yoga - anything that keeps you moving helps.

Find your community. Whether it’s online forums, local support groups, or a therapist who understands MS, you don’t have to do this alone. Fatigue and brain fog are invisible - but you’re not imaginary.

If you’re worried you might have MS - don’t ignore symptoms. See a neurologist. Get an MRI. Early action changes everything.

MS is not a death sentence. It’s a life-altering condition - but with the right tools, many people live full, active lives. The science is on your side. The treatments are better than ever. And the future? It’s brighter than it’s ever been.

There are 8 Comments

Patty Walters

i got diagnosed last year and honestly? the fatigue is worse than the numbness. i used to think it was just laziness, but no-it’s like my body’s running on 2% battery and someone keeps unplugging the charger. i started taking vit d and it helped a little, but the brain fog? still there. sometimes i forget my own phone number. lol.

RAJAT KD

MS is not a death sentence, but it’s a life sentence with no parole. Early treatment saves nerves. Period.

Phil Kemling

It’s eerie how the body turns on itself. We evolved to fight infections, not to mistake our own insulation for enemy fire. The immune system isn’t broken-it’s confused. And if you think about it, that’s the tragedy of autoimmunity: the very thing meant to protect you becomes your greatest threat. We’re not just fighting a disease. We’re fighting a miscommunication inside our own biology.

Diana Stoyanova

okay but let’s talk about how wild it is that gut bacteria might be part of this?? like, i’m sitting here eating my kombucha and suddenly i’m like-wait, is my kimchi saving my nerves?? i’ve been doing yoga, walking daily, and taking 5k IU of D3, and honestly? my brain fog is less like a fog and more like a light mist now. if you’re reading this and you’re scared-your body is still fighting for you. even on the bad days. even when the words won’t come. you’re not broken. you’re just rewiring. and science is catching up. we’re not alone in this.

Jenci Spradlin

the infusions are a nightmare to get approved for. insurance says ‘try the pill first’ even if the pill wrecked your liver. then they say ‘oh you’re on the infusion now? cool, we’ll only cover it if you’ve had 3 relapses in 2 years.’ like, i’ve been walking sideways for 18 months and you want me to fall again before you help? ridiculous.

Meghan Hammack

you’re not lazy. you’re not crazy. you’re not making this up. i’ve been there. the fatigue? real. the brain fog? real. the guilt? real. but you’re still you. still strong. still worthy. keep moving. even if it’s just 5 minutes. you’re doing better than you think.

tali murah

Oh, so now we’re blaming Epstein-Barr and vitamin D? Let me guess-next they’ll say MS is caused by not drinking enough kale smoothies and hugging trees. People with MS aren’t victims of a ‘perfect storm.’ They’re victims of bad luck, bad genes, and a medical system that treats them like a puzzle to be solved, not a person to be helped. And don’t get me started on the $80,000 drugs that only work for ‘ideal’ patients. Meanwhile, the rest of us are just trying to remember where we put our keys.

Ian Long

to the person who said they forget their phone number-i’ve done that too. and i’ve also walked into rooms and forgotten why. but here’s what i learned: it’s not your fault. it’s not weakness. it’s biology. and if you’re still here, still reading, still trying? you’re winning. not because you’re cured. but because you’re still fighting. and that’s enough.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *