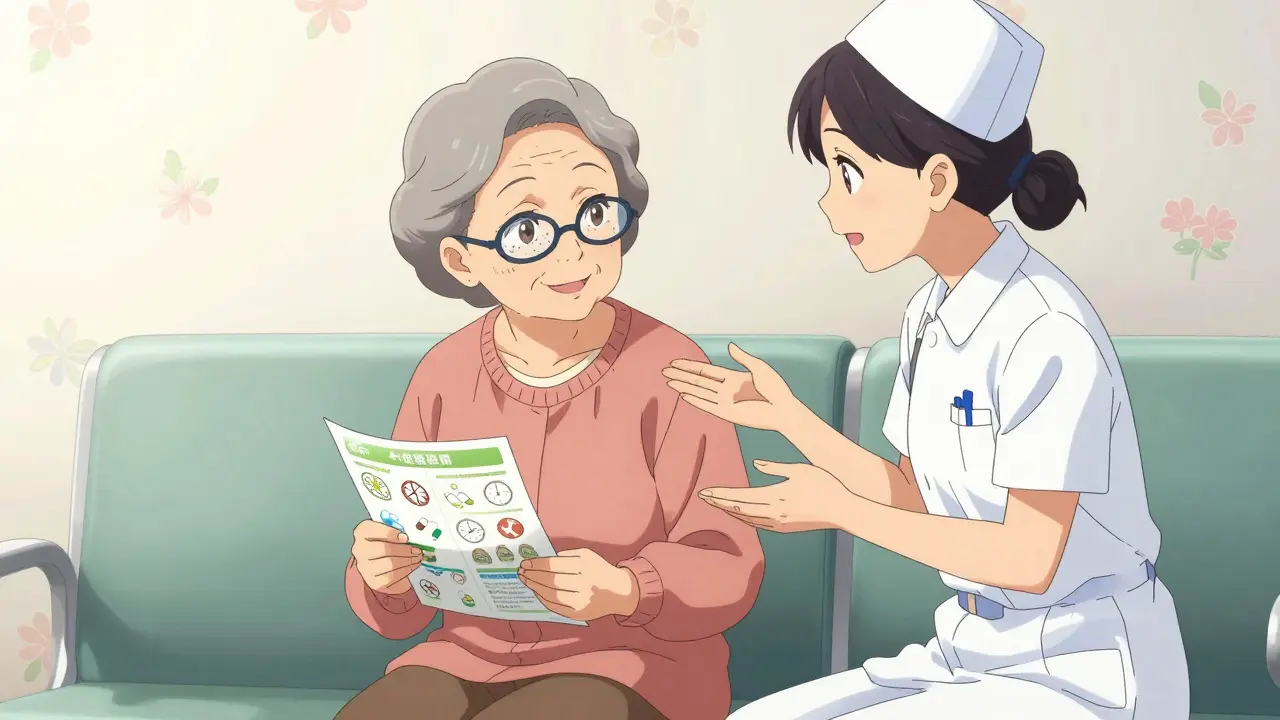

Why senior patient education matters more than ever

By 2030, one in five Americans will be over 65. That’s not just a number-it means more older adults navigating complex medical systems, managing multiple medications, and trying to understand doctor visits they barely remember. Many of them are confused. Not because they’re not smart, but because most health materials are written for someone who reads at a 7th or 8th grade level. For many seniors, that’s too high. The truth? About 71% of adults over 60 struggle with basic health print materials. That’s why senior patient education isn’t optional-it’s a lifeline.

What makes good health material for older adults?

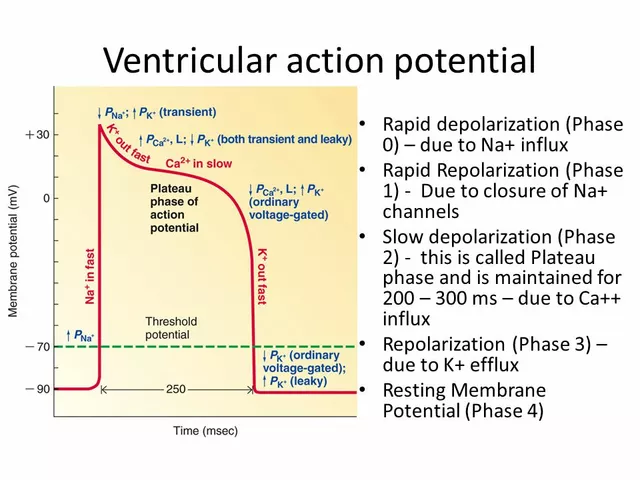

Good senior patient education doesn’t just use simple words. It’s built around how older adults actually experience health information. Vision changes mean small text is unreadable. Memory issues mean they forget instructions after leaving the clinic. Hearing loss makes verbal explanations unreliable. So effective materials do three things: they simplify, they repeat, and they show.

Font size matters. The National Institute on Aging says 14-point or larger is the minimum. No exceptions. Arial or Verdana are better than Times New Roman because the letters are clearer. Line spacing should be at least 1.5. Black text on white background works best-no pastel colors or busy backgrounds. Pictures aren’t decoration; they’re instruction. A drawing of how to hold an inhaler is worth 500 words.

Numbers are tricky. Saying “take 2 pills twice a day” is confusing. Better: “Take one pill in the morning and one at night.” Use clocks or sun icons to show timing. Avoid percentages, fractions, or complex math. If you must use numbers, write them out: “five” instead of “5.”

What resources actually work?

Not all websites or pamphlets are created equal. The best ones follow the universal precautions for health literacy-a set of standards that assume everyone might struggle with health info, so you design for the lowest common denominator. Here are trusted sources that get it right:

- HealthinAging.org by the American Geriatrics Society: Over 2.3 million people use this site yearly. Their materials on diabetes, heart failure, and dementia are written at a 4th-grade level with clear icons and real-life photos.

- MedlinePlus Easy-to-Read: The National Library of Medicine’s section has 217 verified resources, from “How to Use a Blood Pressure Monitor” to “Understanding Your Medicare Plan.” All are tested with seniors before publication.

- NIA’s Talking With Your Older Patients: This isn’t just for patients-it’s a guide for doctors and nurses. It teaches how to slow down, use plain language, and check understanding with the “teach-back” method.

- CDC’s Health Literacy Toolkit: Offers printable one-page guides on topics like medication safety and fall prevention. Each includes a QR code linking to a short video in plain English.

How to use the teach-back method

Doctors often ask, “Do you understand?” and get a nod. But nodding doesn’t mean learning. The teach-back method fixes that. Instead of asking if they understand, ask them to explain it back in their own words.

Example: After explaining how to take blood pressure medicine, say: “Can you tell me how you’ll take this pill each day?” If they say, “I’ll take it when I feel dizzy,” you know you need to try again. Don’t correct them. Say: “Let’s go over that one more time.”

Studies show this simple technique improves medication adherence by 37%. It takes less than a minute. Yet only 28% of U.S. clinics use it regularly. That’s a missed opportunity.

Why videos and voice matter now

More seniors are using telehealth. In 2023, 68% of older adults had a virtual doctor visit-up from just 17% in 2019. But many struggle with apps, passwords, and buttons. That’s why new materials combine video with audio narration.

The NIA’s updated Go4Life program now includes voice-guided exercise videos. You can press a button and hear instructions in a calm, clear voice. No reading required. HealthinAging.org added 47 new resources in 2023 specifically for people with mild memory loss-using repetition, slow pacing, and visual cues.

Even simple tools help. A family member can record a 90-second video of the patient’s own doctor explaining their medication schedule. Play it back on a tablet. Seniors remember what they see and hear far better than what they read.

What doesn’t work-and why

Many clinics still hand out thick booklets with tiny print, medical jargon, and 10-step instructions. These are useless. One study found that 63% of seniors couldn’t read their own medication labels. Another 51% didn’t ask for help because they were embarrassed.

Don’t assume they’ll look things up online. Only 41% of seniors over 75 use the internet regularly for health info. And if they do, they’re often overwhelmed by ads, pop-ups, and complex websites.

Also avoid: acronyms (like “HbA1c”), long paragraphs, passive voice (“Medication should be taken”), and abstract concepts (“Maintain optimal glycemic control”). Say: “Take your sugar pill every morning with breakfast.”

How to create your own materials

If you’re a caregiver, nurse, or community worker, you can make better materials without a big budget. Start with these steps:

- Write your message in plain English. Use short sentences. No more than 15 words per sentence.

- Replace medical terms. “Hypertension” → “high blood pressure.” “Diabetes mellitus” → “diabetes.”

- Add pictures. Use free stock photos from CDC or NIA. Show real people, not clip art.

- Test it. Find five older adults. Read it to them. Ask: “What’s the main thing you’ll remember?” If they don’t say the key point, rewrite it.

- Print in large font. Use 14-point or bigger. Double-check contrast.

It takes time, but one well-made handout can prevent a hospital visit. The CDC says materials tested with real seniors reduce confusion and errors by up to 42%.

The big picture: Why this saves money and lives

Bad communication costs money. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates poor health literacy adds $106 billion to $238 billion to U.S. healthcare costs every year. Older adults are the biggest part of that bill.

Hospitals that use good senior education tools see 14.3% fewer readmissions. That’s $1,842 saved per patient. Medicare is taking notice. Funding for health literacy programs is expected to jump from $187 million in 2023 to $312 million by 2027.

But the real win isn’t money. It’s dignity. It’s knowing your pills, understanding your condition, and feeling confident asking questions. When seniors can manage their health, they stay independent longer. They live better. That’s the goal.

What’s next for senior patient education

The future is personal. The National Institutes of Health is funding a $4.2 million project to build AI tools that adapt health info based on how a person hears, sees, and remembers. Imagine a tablet that changes font size automatically, reads aloud in a slow voice, and repeats instructions if the user looks confused.

Medical schools are also changing. By 2026, all U.S. med students must complete 8 hours of health literacy training. That means the next generation of doctors will know how to talk to older patients-not just what to tell them.

For now, the tools are already here. You don’t need fancy tech to make a difference. Just clear words, big print, and the patience to let someone say it back.

What reading level should senior patient education materials be written at?

Materials should be written at a 3rd to 5th grade reading level. This matches the needs of about 20% of U.S. adults who read at or below this level, even though the national average is higher. Studies show comprehension improves by 42% when materials are simplified to this level for adults over 65.

How big should the font be in printed senior health materials?

Use at least 14-point font. The National Institute on Aging recommends this minimum for readability. Avoid small fonts like 10 or 12 point-even if they look fine to younger people, many seniors with vision changes can’t read them. Larger is better, especially for medication instructions.

What’s the teach-back method and why is it important?

The teach-back method asks patients to explain instructions in their own words. Instead of asking “Do you understand?”, say “Can you tell me how you’ll take this medicine?” This catches misunderstandings early. Research shows it improves medication adherence by 37% and reduces errors. It takes less than a minute and works even with memory issues.

Are videos better than written materials for seniors?

For many seniors, yes. Videos with clear voiceovers and simple visuals help those with reading or vision challenges. The CDC and NIA now include video links with printed materials. A 90-second video showing how to use an inhaler or check blood sugar can be more effective than a 2-page handout. Audio narration with slow pacing works especially well.

Where can I find free, reliable senior health materials?

Start with HealthinAging.org (by the American Geriatrics Society), MedlinePlus Easy-to-Read (from the National Library of Medicine), and the CDC’s Health Literacy Toolkit. All are free, evidence-based, and tested with older adults. They cover common conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and dementia using plain language and clear images.

Why do seniors avoid asking questions at the doctor?

Many feel embarrassed or fear being seen as stupid. A 2022 survey found 51% of older adults never asked for clarification-even when they didn’t understand. Others assume the doctor will repeat it. The key is creating a safe space. Doctors who use phrases like “Most people have questions about this” help reduce stigma and encourage honest conversation.

There are 10 Comments

Anu radha

My aunt in Delhi can't read her medicine labels. Big font, simple words, and voice help so much. No jargon. Just love and patience.

Sachin Bhorde

Man, I’ve seen this in my clinic-seniors nodding like robots while totally lost. Teach-back isn’t just good practice, it’s clinical hygiene. Skip it and you’re just gambling with their lives.

Joe Bartlett

Brits do this right. Big print, clear voiceovers, no fluff. Why can’t the US just copy us?

Marie Mee

They’re hiding something. Why are they pushing videos so hard? Is Big Pharma controlling the NIA? I saw a guy on YouTube say they’re tracking what seniors watch

Sam Clark

Thank you for laying this out with such clarity. The emphasis on testing materials with actual seniors is the most critical point-not just for compliance, but for dignity. Too many programs are designed in a vacuum, then handed out like brochures at a dentist’s office. Real people, real feedback, real change. This isn’t just education-it’s equity.

Steven Lavoie

As someone who’s worked with elders across cultures-from rural Appalachia to urban Mumbai-I can say this: simplicity transcends language. A picture of a pill bottle next to a clock, with a sun and moon, speaks louder than any brochure. And yes, the teach-back method? It’s not a trick. It’s respect in action.

Salome Perez

There’s something profoundly beautiful about slowing down enough to let someone else find their words. In a world obsessed with speed and efficiency, this approach-big fonts, quiet voices, repeated cues-isn’t just practical, it’s poetic. It says: you matter. Your understanding matters. Your dignity matters. And that, more than any statistic, is what will change the landscape of elder care.

Chris Van Horn

OMG this is the most obvious thing ever and yet 90% of hospitals are still handing out 8-point font pamphlets written by lawyers. Are they trying to kill old people? I saw a guy in the ER last week holding a med sheet upside down because he couldn’t read it. He was 78. He didn’t ask for help because he was ‘too embarrassed.’ That’s not a mistake. That’s a crime.

Michael Whitaker

While I appreciate the sentiment behind this piece, I must respectfully challenge the underlying assumption that seniors are inherently cognitively diminished. Many of them are retired physicians, engineers, professors-individuals who once shaped institutions. To reduce their capacity to comprehension levels based on arbitrary grade scales is not only condescending, it is a misrepresentation of cognitive resilience in aging. The real issue is not literacy-it is institutional arrogance. Why not design materials that honor intellectual autonomy rather than infantilize through oversimplification?

Peter Ronai

Oh please. You think this is new? I’ve been yelling about this since 2012. The CDC’s toolkit? That’s 2018 stuff. And don’t even get me started on MedlinePlus-they still use that awful blue background on their PDFs. And AI? Please. We don’t need AI to read aloud. We need doctors who aren’t rushed. We need Medicare to pay for 15-minute follow-ups. Not apps. Not videos. People. That’s what’s missing. And nobody wants to fix that because it costs money and requires actual human effort. So we get cute infographics instead.

Write a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *